Johnny Greer’s Blues - Part 1

Generated Image

The Devil don’t care about your soul, son. He’s got more than he can handle as it is. Been that way for a long time. Way before I was born, that’s for sure.

So, when people try to say I sold my soul to Satan, I just have to laugh, ‘cause if I didn’t I’d have to think on why they believe that. They don’t ask about soul selling when it comes to the white boys like Clapton or Van Halen, so why do they think that about folks like me and Robert Johnson before me. You do the math on that.

No, I didn’t sell my soul. I was always good. Hell, I’m still good. You know that just like everybody else. Here I am pushing 80, and they all say I’m one of the best. Not bragging, just reporting the news.

And, while I’m here telling you truths, I think I gotta tell you a little something. Like I said, I didn’t sell my soul to nobody, but that’s not to say I didn’t make any deals I regret along the way.

*****

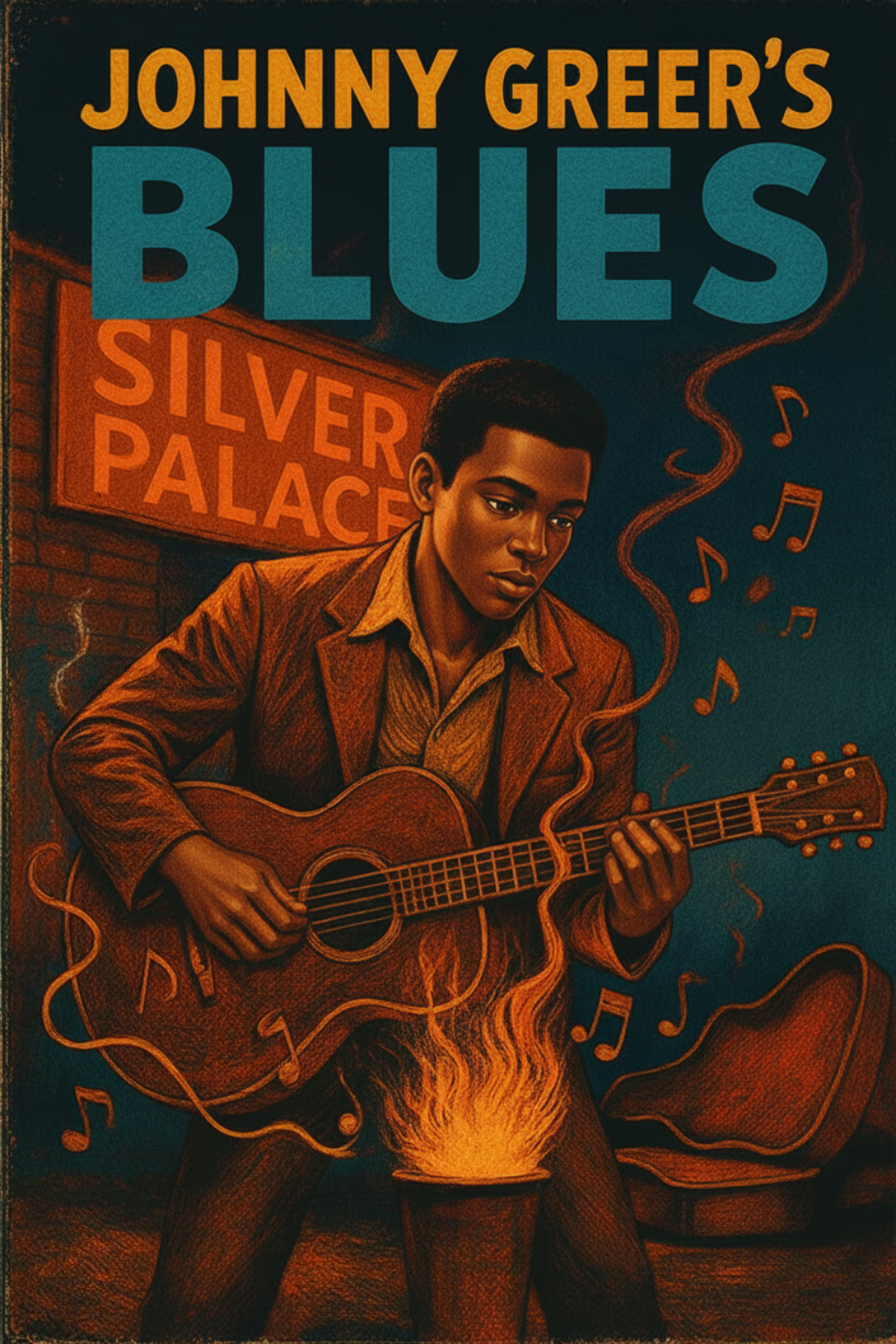

In 1971, Johnny Greer, a 20 year-old Black kid from outside of Birmingham hitched his way to Memphis with little more than the clothes he was wearing and an old acoustic guitar in a battered black case. He’d got those from his uncle when he passed a few years before. His uncle Dan had played for years in clubs around the south under the name Danny B. When he started out, the clubs were legally segregated, and by the time he stopped playing they were still segregated, if not by technical force of law.

Danny B. was not famous or rich, but he was good. He took a shine to his nephew, and taught him how to play when Johnny was 15.

“You got the stuff,” Uncle Danny told him. “I want you to practice, you hear?”

Danny gave his nephew a cheap no-name guitar with nylon strings he had lying around his house, and Johnny played it every day after school. His parents more or less ignored his playing, but they didn’t stop him.

By the time Danny died of lung cancer - too many years of smoking too many cigarettes- Johnny was pretty good.

Johnny visited Uncle Dan in the hospital before he died. “Listen, Johnny. Here’s what you got to do. When I die, and that won’t be long, you go to my house and get my guitar. My real one that I keep in that old black case in my room. Take it and get yourself out of this town. Ain’t nothing in Birmingham that’s going to help you. Take yourself to Memphis. I got a friend named Pete who owns a bar in South Memphis over near Stax recording studio. It’s called the Silver Palace. Lots of musicians play there and drink there. Tell Pete you know me, and he’ll let you play an open mic. If things work out, someone will pick you up for paying gigs. It’s the right way to go for you and your talents, Johnny. Nothing will come of them here, that’s for sure.”

Uncle Dan was gone within a week. After the funeral, Johnny did what his uncle told him to do. He grabbed the steel-string acoustic in its faded and beat up black case, and made his way to Memphis.

His first night in town he found the Silver Palace in South Memphis. It was on East McLemore, within sight of the red neon Stax Records sign. Johnny could practically hear Isaac Hayes just talking about Shaft in the night as he made his way into the small brick building with a faded wooden sign that read “Silver Palace.”

The packed bar exploded with music when Johnny walked in. Customers backed the bar and the dozen or so tables. A small raised stage - no more than a couple of feet off the floor - was opposite the entrance. The smell of cigarette, pot, and cigar smoke hung in the air, mixed with the sour aroma of cheap whiskey and spilled beer. Dim shafts of light from the ceiling cut through the haze and barely illuminated a young guy was playing and singing “Born Under a Bad Sign.” In front of the stage a few people danced and others stood and talked.

Johnny was in love with the place.

“You playing?” someone said behind him.

“What?” Johnny asked, turning to see an older man in a wide-lapeled jacket and white shirt with three buttons undone.

“You got that guitar. I assume you want to play the open mic. Hate to disappoint you, but the list is full.”

“Hey, you know Pete?” Johnny asked.

“Pretty well, in fact. Pete is me.”

Johnny introduced himself and told him about his uncle, and Pete lit up. He held up his hands and said “If you’re Danny B’s family, you’re my family. You can play.”

“Tonight?”

“Yeah, son. Tonight. Just listen for your name. Oh, and you better be good. They might just tear you apart if you aren’t.”

Pete offered him a drink - on the house, and told him to just enjoy the show until it was his turn. Pete introduced all the acts, giving appropriate praise or thinly veiled criticism as warranted.

Most of the musicians who played were good. Some were real good. A lot of them played stuff from the Stax or Volt labels. A few played some Motown tunes. Nobody played the Beatles.

A good looking female singer finished up a version of “Where Do I Go?”, a song from the Hair soundtrack that Carla Thomas covered on her Memphis Queen album. The singer did alright, but the song didn’t sell without the orchestra back up. All she had was what appeared to be her boyfriend with a single horn. Still and all, not bad.

Johnny politely clapped when Pete called him up to the stage.

Johnny walked to the stage, feeling the eyes boring into him. Something in him wanted to run. That part told him the audience would hate him and run him back to Alabama that night. He had no business doing this.

But the other part thought he just might be okay. And Johnny figured he might as well give it a try. Worst that could happen is he would have to go back home. And that wasn’t so bad, really.

Johnny fumbled at the case and pulled out his uncle’s guitar.

“Evening, folks. I’m Johnny Greer, and I’d like to play an old Furry Lewis song about some creepy crawlies. This is “Mean Old Bedbug Blues”.

He could hear some laughs coming from the audience. They weren’t here for the blues. He knew that. But that didn’t throw him.

What almost did was the white dude who entered the bar just before he started to play. He could make out that the man was well dressed, tall and heavyset. The other thing that rattled him is that no one seemed to even notice this lone white face in the crowd.

“Umm..thank you,” Johnny said as he started playing the blues progression and singing about the jackass sized bedbug that ruined his sleep. But he didn’t play it straight. Somehow, he transitioned from straight blues to an almost rock and soul fusion. It didn’t take but a few seconds for the laughing to stop, and by the time Johnny finished the crowd was on its feet cheering for him.

He’d never felt anything like it.

After Pete introduced the next act he led him to the bar and said, “I knew ol’ Danny B. wouldn’t send no garbage my way. You come back next week, Johnny. I’ll make sure there are some people here to see you. You’re going to find yourself in a band before you know what hit you!”

As Pete walked off, the tall white man sidled up to him. “He’s right, Johnny. You’re good.”

Johnny looked at him. The man was tall, clean cut and impeccably dressed in fancy suit. Johnny couldn’t believe that no one else was looking at this man, who stood out like a sore thumb. Hell, he stood out more than a whole hand full of sore fingers.

“Howard Gold,” the man said holding out his hand to shake Johnny’s. “I’m an agent out of New York. I’m not going to waste any of your time or mine, Mr. Greer. I want to sign you as a client immediately.”

Johnny looked at him and gulped. Now, Johnny was a kid and probably naive, but even he knew this couldn’t be on the level.

As if reading his mind, Gold handed him a card.

“My office number in New York is on there, and I wrote the name and number of the hotel I am staying at for the next couple of nights before I fly back. Ask around about me and call me. I can get you with a label within the month.”

The man clapped him on the shoulder, and walked out.

After the last performer of the night, Johnny asked Pete if he had seen the man talk to him. Pete said no, and Johnny asked if he was sure.

“Pretty sure I’d have seen a white man in here, Johnny. It would have stuck in my head.”

“Okay, but you ever hear of a Howard Gold. Says he’s an agent?”

“Who’s he with?”

Johnny looked at the card. “Says he’s with the Musical Artist Agency in New York.”

Pete grabbed the card and whistled. “Yeah, that’s a real agency. One of the top ones. Their clients do well. Real well.”

“So should I call him?”

“Hell yes, you should call him. Just be careful. A lot of these agents will try to rip off a young artist. Or any artist. Just hear the man out and if he offers you a deal make sure it’s fair and right.”

Johnny nodded.

“You had a real good first night in the music business, son. Your uncle would be proud. Just be careful. Don’t let these guys get you to sell your soul. You know how that turned out for Robert Johnson.”

Part Two will follow in the next installment.

If you want to support my writing, one of the best ways to do it now is to subscribe to my Substack or buy one of my books. For now, I will keep putting stuff here for free, but will pull the pieces down after a month or so. I’ll keep the full archive of ongoing work available on Substack for paid subscribers. So, if you think this is worth a few bucks and you like receiving the content as a newsletter, give it a shot. You can get a seven-day free trial to see if it’s worth it to you.